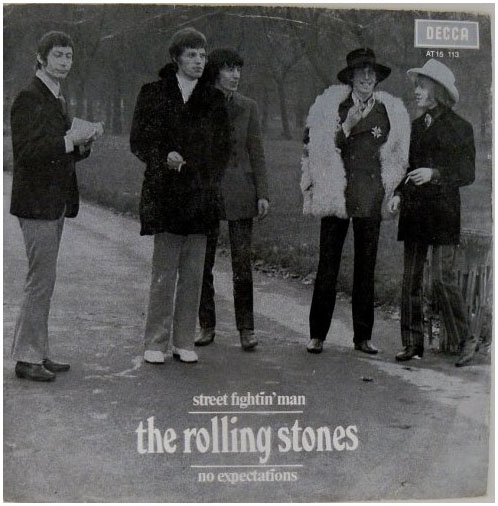

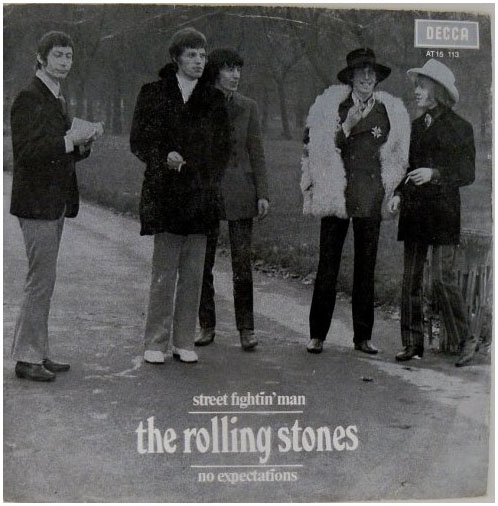

| Notes and Quotes: "Street Fightin' Man" |

|

| In this first recording produced by

Jimmy Miller for the Stones, he helps them rediscover their rock and blues roots. (They released "Jumpin' Jack Flash" first, even though they recorded it later.) The BBC decided to ban the recording, fearing it would fuel the social violence that was wracking the UK and Europe. Decca would not release it until 1971, at which point the Stones were no longer signed with them. |

| One technique he used for

getting a cruder guitar and drum sound was to record the guitar on a cassette recorder.

(Cassette recorders were still rather new and had poor recording quality.) The drum kit is also a small portable jazz kit. |

| Watts. "Street Fighting Man" was recorded on Keith's cassette with a 1930s toy drum kit called a London Jazz Kit Set, which I bought in an antiques shop, and which I've still got at home. It came in a little suitcase, and there were wire brackets you put the drums in; they were like small tambourines with no jangles... The snare drum was fantastic because it had a really thin skin with a snare right underneath, but only two strands of gut... Keith loved playing with the early cassette machines because they would overload, and when they overload they sounded fantastic, although you weren't meant to do that. We usually played in one of the bedrooms on tour. Keith would be sitting on a cushion playing a guitar and the tiny kit was a way of getting close to him. The drums were really loud compared to the acoustic guitar and the pitch of them would go right through the sound. You'd always have a great backbeat. (According to The Rolling Stones. Chronicle Books. 2003) |

| Keith Richards: "Street Fighting Man" is one of my favorite Rolling Stones songs—probably because the music came together through a series of accidents and experimentation. We recorded it in a totally different way than anything we had done up until that point and the results were pretty exciting and unexpected.

|

| The music came first—before Mick [Jagger] wrote the lyrics. I had written most of the melody to "Street Fighting Man" sometime in late 1966 or early '67—before "Jumpin' Jack Flash"—but I couldn't figure out how to get the sound I wanted. It's hard to explain. If you think of a melody as a song's shape, then the sound is its texture. The two were inseparable in my mind. I tried recording the melody in the studio in '67 but nothing happened. So I took the concept home to my Redlands farmhouse in Sussex, England, to work on it.

|

| Around this time, I became fascinated by one of the early cassette tape recorders made by Philips. The machine was compact, so it was portable, and it had this little stick microphone, which would allow me to capture song ideas on the fly. So I bought one, but as I watched the small tape-cartridge reels turn, I began to think of the machine not as a dictation device but as a mini recording studio. The problem is I couldn't use an electric guitar to record on it. The sound just overwhelmed the mike and speaker. I tried an acoustic guitar instead and got this dry, crisp guitar sound on the tape—the exact sound I had been looking for on the song.

|

| At the time, I was experimenting with open tunings on the guitar—you know, tuning the strings to form specific chords so I could bang out the broadest possible sound. That's how I came up with "Street Fighting Man's" opening riff—even before I bought the Philips. I based the rest of the song's melody on the tone pattern of those odd sirens French police cars use [sings the siren and lyrics to illustrate].

|

| Sometime in early '68, I took the Philips recorder into London's Olympic Sound Studios and had Charlie [Watts] meet me there. Charlie had this snap drum kit that was made in the 1930s. Jazz drummers used to carry around the small kit to practice when they were on the bus or train. It had this little spring-up hi-hat and a tambourine for a snare. It was perfect because, like the acoustic guitar, it wouldn't overpower the recorder's mike. I had Charlie sit right next to the mike with his little kit and I kneeled on the floor next to him with my acoustic Gibson Hummingbird. There we were in front of this little box hammering away [laughs]. After we listened to the playback, the sound was perfect.

|

| On that opening riff, I used enormous force on the strings. I always did that and still do. I'm looking at my hands now and they look like Mike Tyson's. They're pretty beat up. I'm not a hard hitter on the strings—more of a striker. It's not the force as much as it is a whip action. I'm almost releasing the power before my fingers actually meet the strings. I'm a big string-breaker, since I like to whip them pretty hard.

|

| Once Charlie and I had the basic track down, we played back what we had recorded through an extension speaker with a recording mike in front of it. We put that track onto an eight-track recorder, which gave us seven additional tracks for overdubbing. That damn little Philips recorder: I realize now I was using it as a pickup for the acoustic guitar—only it wasn't attached to the instrument. |

| Then Charlie added a bigger bass drum on one track, and I added another acoustic guitar to widen the sound. In fact, the only electric instrument on the entire recording is the bass. Bill [Wyman] wasn't around and things were moving fast, so I just recorded the bass line I had in my head. Everything happened so quickly. Dave Mason [of the band Traffic] came in later to add a bass drum and a shehnai [a South Asian oboe] at the end of the song. Brian [Jones] played sitar and tambura and Nicky Hopkins added the piano part. |

| Early on, when I had played the tape of my melody for Mick, his lyrics were about brutal adults. We recorded them and called the song, "Did Everyone Pay Their Dues?" But we weren't that crazy about the results, and the lyrics underwent several rewrites once we saw what was going on in the streets in London and Paris in 1968. While we were in the studio, Mick had been at a huge demonstration against the Vietnam War in London's Grosvenor Square in March. And we were both in Paris in May during the violent protests by students demanding reforms. The French cops were pretty nasty about it. As we traveled around, Mick and I would look at each other and realize something big was happening in two major capitols of the world and that our generation was bursting at the seams. |

| Mick knew that "Dues" needed an overhaul that better matched what was going on. I came up with the line, "What can a poor boy do" and threw it out to Mick. He completed the thought with " 'Cept to sing for a rock 'n' roll band" and he wrote the rest of the new lyrics in the studio. That's how we often worked. One of us would have a piece of a lyric that sounded interesting, then hand it off to the other to get things going. |

| I love the songwriting process, but I really don't like writing by myself. I love the bounce of one person's ideas off the other. Mick wrote down a ton of lines. Then we tore the lines into strips and moved them around. Reams of pages were flying around—and some of them wound up burned [laughs]. Eventually they took shape and we laid down the vocal tracks. |

| Like any of our songs, "Street Fighting Man" not only had to hold together musically and tell a story but it also had to work for a certain bunch of guys who played a very specific way. We had to make sure that what we came up with was something the other guys could get behind. For instance, if Charlie had turned up his nose at what we came up with, I knew the song wouldn't have worked. But he loved it. |

| Actually, I think "Street Fighting Man" is Charlie's most important record. Listen to him on there—he has this Wall of Sound thing going the way he's hitting that snap kit and the bigger drum. When you experiment the way we did as a band, the smallest little things can happen that turn out to be a big deal. You just need the determination to go there. It's amazing what can happen when you have the right instruments—and the right amount of echo [laughs]. To his credit, our producer, [the late] Jimmy Miller, brought incredible enthusiasm to what we were doing on "Street Fighting Man." He was one of the warmest guys and an incredible friend. We made our best records with him. He always knew when to engage and when stay out of the picture. He knew I was going for something special on the song and interjected only when he thought we were losing it and needed a break. |

| "Street Fighting Man" was the first time I had a sound in my head that was bugging me. That would happen again many times, of course, but after that song I knew how to deal with it. Only in the studio could I put the two things together—the minimalist sound and the overdubbing. That's where the vision met reality. When we were completely done recording "Street Fighting Man" and played back the master, I just smiled. It's the kind of record you love to make—and they don't come that often. |

| "Keith Richards: 'I Had a Sound in My Head That Was Bugging Me'." Wall Street Journal, 11 December 2013. [http://m.us.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303497804579238550068715652?mobile=y; accessed December 2013] |

|

| Schedule |

|

13 December, 2013

|