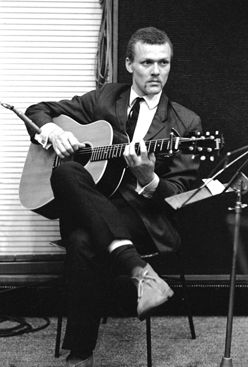

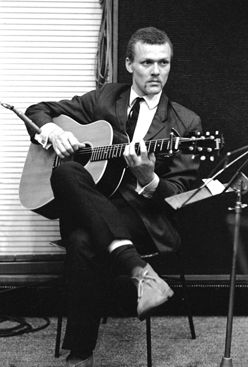

Davey Graham © |

|

| b. David Michael Gordon Graham, Market Bosworth, Leicestershire, England, 26 November 1940 |

| d. 15 December 2008 |

Perhaps fittingly, a pivotal figure in the transformation of the 1960s British folk music scene may never have felt entirely part of it (see McMullen 1991, Pilgrim 2008, and Denselow 2008). Born into a multilingual, multiethnic family—the son of a Scottish father who taught Gaelic in London and a Guyanese mother—David Graham (b. 1940) grew up in the racially charged Notting Hill Gate area of London. Strongly believing in the power of learning languages, his parents enrolled him at the Lycée Français in Chelsea, which unfortunately was where a playground accident cost him a majority of the sight in his right eye. |

| He began learning classical guitar at 12, studying with Oliver Hunt (later of the London College of Music) and gaining a unique approach to the instrument. When his parents could afford his first guitar, the teen took to playing along with blues records (notably Big Bill Broonzy), but his intellectual curiosity also led him to listen to modern jazz (e.g., Thelonious Monk) and to continue learning classical pieces (Graham 1963). Along the way, he developed a style of playing that applied classical techniques (notably the independent use of the right-hand’s individual fingers rather than just strumming) to playing blues, jazz, and folk repertoires. |

| |

| 1962 (age: 21-22) |

| His eclecticism also attracted the attention of Alexis Korner with whom he recorded a disc released by Topic Records (where Bert Lloyd served as Artistic Director) in 1962 with Bill Leader as the producer. The three items on the disc offer early examples of his polyphonic solo guitar arrangements, heard especially well in his “Angi,” which would prove a benchmark for young folk guitarists eager to demonstrate their technical proficiency. Although he would play with both Blues Incorporated and with electric blues proponent John Mayall, Graham preferred working as a soloist or accompanist, and it would be in these roles that his reputation spread. |

| "Anji" (D. Graham) |

| |

| 1963 (age: 22-23) |

| In May 1963, Hugh Mendl recorded a concert by the Thamesiders with Graham showcasing his solo performances of “She Moved through the Fair” and “Mustapha,” which foreshadow both the Celtic music movement and the incorporation of non-Western musical ideas into Western musical contexts. |

| |

| 1964 (age: 23-24) |

| In July 1964, Graham and singer Shirley Collins performed at the Mercury Theatre advertised as a program with an “Eastern flavour.” Ever eager to catch the next big thing, Mendl—who had moved up the administrative ladder at Decca—heard possibilities and encouraged his colleague Roy Horricks to produce an album: Folk Roots, New Routes (1964), a mix of traditional European folk songs (e.g., “Lord Gregory”) and jazz (e.g., the instrumental “Blue Monk”). Horricks followed this record with another influential solo Graham project: Folk Blues and Beyond that Decca released in January 1965 and that again illustrated the musician’s broad tastes in musical styles. In addition to a cover of Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” the disc included his “Maajun (a Taste of Tangier).” Although the album would have been off the radar of most listeners, musicians took notice, including Dave Davies of the Kinks who attempted to apply some of Graham’s ideas when working on “See My Friends” (Davies 1996, 75). |

| "Maajun (a Taste of Tangier)" (D. Graham) |

| |

| 1965 (age: 24-25) |

| Graham should have been one of the best-known performers in the wave of folk and folk-inspired British musicians to emerge in 1965; however, several factors prevented him from gaining widespread popularity. Visually, he did not look like a mid-sixties British pop star in its most ethnically narrow white male stereotype. First, his close-cropped hair and elongated moustache more closely approximated a military figure than many contemporary standards of pop-star male beauty and Afro hairstyles would not become acceptable until the second half of the sixties. Second, photographers always worked to avoid placing his damaged right eye clearly in the frame. Musically, as dexterous as his guitar playing was, his voice lacked the range, agility, and expressiveness of successful performers. Consequently, he composed few items that involved singing, thus limiting his audience. |

| |

|

| At a more dysfunctional level, as a devotee of cool jazz, Graham purposely addicted himself to cocaine and heroin in imitation of his musical heroes. As a result, his ability to show up for gigs and to be able to perform suffered and promoters shied away from booking him. Similarly, musicians such as Shirley Collins refused to perform with him, not knowing which Davey Graham would be on stage with them. He would continue his trips to North Africa and would begin learning the Indian stringed instruments the sarod and the sitar, but his career became one of unfulfilled promise. |

| Networks of interacting individuals with diverse cultural preferences and biases shaped the course of musical change in 1960s British popular music. Davey Graham may have been the innovator, but his demeanor and sheer virtuosity intimidated many. Scottish folk singer Danny Kyle (b. 1939) remembers that while “you could go and sit in total awe of the man,” he favored a slightly younger musician; someone “you would go and listen [to] and you would say to yourself, ‘Here, perhaps I could do some of that’ because he made it seem attainable” (Harper 2000). |

| |