| |

Politics and Economics: Rule

Britannia, Britannia Rules the Waves . . . . |

| Between the seventeenth and

twentieth centuries, Britain established

herself as a world power, if not the world power. At the foundation of

this power was her symbiotic success as a naval force and as the world's

merchant. By the nineteenth century, the maxim that "the sun never set

on the British Empire" reflected the knowledge that not only had she colonies

in the Americas, Asia, and Africa, but also that English and Scottish

merchants operated in almost every major city of the world. Not that this

power went unchallenged. France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, and Russia,

and eventually the Americans and Japanese, all sought to secure sources

for raw materials to supply their industries. Eventually, they also sought

additional markets for the goods their factories produced. Nevertheless,

Britain was the big kid on the block and her navies ensured that her merchants

had best access to the world. |

| While this mercantile-military

machine generated vast sums for both the aristocracy who originally underwrote

many of these ventures and for the merchants who did the actual work,

the entire system relied upon an underclass. Navies and merchant fleets

need sailors. Factories and mines need laborers. And armies need soldiers.

As Britain confronted both the peoples whom she sought to colonize and

those with whom she was in competition, she sacrificed generation after

generation of young men (and women) to the dominatrix of prosperity. |

| The cycle of war and peace

eventually brought the empire down in the twentieth century, first through

the so-called "Great War" (the "war to end all wars") and ultimately in

World War II. Between 1938 and 1945 the United Kingdom lost three-hundred and sixty thousand people, saw large

sections of every major (and even some minor) cities destroyed by bombing,

and spent the national purse into debt. The once great economy was shattered

and the once super-power was a shadow of its former self. The governments

of the first half of the twentieth century had seen some of this coming.

They had formed previous colonies into the British Commonwealth in 1931

by luring Canada, Australia, Irish Free State, New Zealand, Newfoundland,

and South Africa into an economic community that largely served the interests

of Britain. However, in the post-war era, they did not have the military

or economic strength to retain their grip on the peoples and nations they

had subjugated. India and Pakistan (1947) and Ceylon [Sri Lanka] (1948)

were among the first to be "given" independence. Burma seceded (1948).

Ireland left the Commonwealth (1949). And through out the fifties and

sixties one colony after another took their independence. |

| However, the post-war years

were hardly safe. The leaders of the Soviet Union and of the United States—the successors to world power after the economic and military decline

of Britain, France, and Germany—redefined the geo-political landscape.

Britain found itself in alliance with the United States, forming the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization in April of 1949 after Stalin had blockaded

the city of Berlin in 1948. On the other side of the Eurasian continent,

a communist China challenged domination of those markets and again, Britain

found itself in alliance with the United States and other United Nations

countries in the Korean War. Indeed, the United States had flourished

as the United Kingdom's principal supplier during World War II and in

the post-war era, was the West's financier. |

| One of the first acts of democracy

for the British after World War II was to vote Churchill and the Conservatives

out and to bring in Clement Attlee's Labour Party (1945-1951). Labour,

faced with a country in economic crisis, nationalized several important

industries (notably banking) and established the basis of a social safety

net for those who were unemployed or unemployable. Britain faced rationing

well into the 1950s and dealt with long-term debt and related problems

of inflation into the 1960s. On top of this, Britain needed to update

its industrial infrastructure. Factories that survived German bombing

often were nineteenth-century antiques designed to process cheap raw materials

from colonies that no longer existed. Churchill saw the need for an economic

union with the rest of Europe, but national pride and an historical sense

of separateness from the mainland thwarted timely moves to join emerging

continental economic institutions such as the European Coal and Steel

Community (ECSC), European Atomic Energy community (Euratom), and European

Economic Community (EEC/Common Market). Even with the return of Churchill

(and later Eden and Macmillan) and the Conservatives (1951-1964),

and an end to rationing and industrial growth found Macmillan's application

for EEC membership rejected (1963)

by DeGaulle and the French. |

| The electorate returned Wilson

and Labour (1964-1970) to power for the remainder of the sixties, but

the timing is important. 1964 was the year of the Beatles. This pop group almost single-handedly resuscitated

British self-assurance, despite a growing trade deficit, slow industrial

growth, and shrinking financial reserves. Even the establishment of wage

and price controls and a tax increase (1966)

and a re-rejected EEC application (Oct 1967)

could not dampen their cultural spirits. Britain, for a while, was the

center of the pop universe. |

|

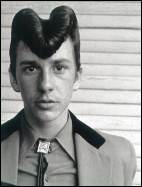

| The Teddy Boy (Tonne

boy?) had his heyday in the mid 1950s and was followed by an even

more Americanized model: the Rocker. Rockers took inspiration from

the likes of Elvis and Buddy Holly—leather jackets and cowboy

shirts—as well as the James Dean/Marlon Brando figures of movies

like The Wild Ones. Another group of working class men with

a radically different image of themselves later challenged the rockers.

Mods were obsessed with clothing, Italian suits and short hair. |

| With the international

decline of British power, Britons who had spent their lives in India

or Africa as public servants or as members of security forces now

had to return to a mother country their children had never known.

Sometimes they headed to Canada or Australia. More often they found

family still living in the United Kingdom and relocated there. However,

they need not have felt great longing for cultures they left behind.

Immigrants from the former colonies (who seem to have decided that

they might as well take advantage of the tax dollars they and their

forebears had paid to "the mother country"), soon joined them. Indian,

Pakistani, and West Indian Emigrants arrived en masse in the fifties

and sixties and settled in and around the major cities. The British,

like other colonial powers, already had a history of treating their

foreign "subjects" as quasi-human. "White" Britain reacted poorly

to the arrival of the "Blacks." Conservative elements of British

society quietly condoned Teddy Boy riots against these immigrants

in Nottingham and in the Nottinghill Gate area of London in 1958

while at the same time finding themselves repulsed by the agents

of aggression. |

| Nevertheless, the arrival

of these peoples had some profound affects upon British urban culture,

and particularly in the area of popular music. White British musicians

in the sixties would increasingly incorporate elements of Jamaican ska

(for example the early recordings of the Spencer Davis Group) and Indian

classical and religious music (George Harrison's compositions for the

Beatles) into their recordings. Previous generations had already adopted

American popular music. Both Paul McCartney's father and Peter Townshend's

mother and father had performed in bands that featured American dance

music in addition to British fare. The forties and fifties saw the British

consume even more American culture while at the same time some of them

found themselves repulsed by the directness. |

| This is not to say they gave

up on the idea that British music, or at least their interpretation, was

superior to the American originals. The dominance of American popular

culture in Great Britain was partly a result of the thousands of Americans

stationed there during the war. They brought with them transmitters for

local broadcasts meant for the enlisted, but listened to by the locals

too. The government sanctioned the British Broadcasting Corporation as

the reasoned voice of culture in the isles, but the Americans and others

(for example, Radio Luxembourg and, later, pirate radio stations such

as Radio London) provided an alternative voice. |

| As Louis Armstrong had inspired

British jazz musicians (for example, Nat Gonella traded on his imitations

of the great "Satchmo"). Other British musicians found New Orleans ("Dixieland")

jazz an inspiration and later performers drew on Americans like Huddie

Ledbetter ("Leadbelly"), Eddie Cochran, and "girl groups" such

as the Shirelles. |